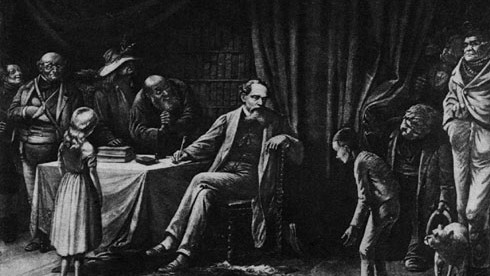

Dickens in the Gallery

Carolyn Quinn writes about Charles Dickens’ time in the Press Gallery in the early 1830′s.

Like many others, Charles Dickens began his literary career as a journalist. His own father became a reporter and Charles began with the journals ‘The Mirror of Parliament’ and ‘The True Sun’ and later he became a parliamentary journalist for The Morning Chronicle .

Dickens was still a teenager when he arrived at Westminster sometime during the session of 1830-31, He’d taught himself the “Gurney” system of shorthand ( a forerunner of Pitman) and started his trade in Westminster providing gallery reports for The Mirror of Parliament, a weekly rival to Hansard which had been started by his uncle John Henry Barrow in 1828. Nearly all the reporters had degrees – most were law students – but Dickens was an exception. His own education had been patchy. His schooling was interrupted when he was 12, when his father was imprisoned for debt. Young was withdrawn from school and forced to work in a warehouse that handled ‘blacking’ or shoe polish to help support the family.

Having got his first position as a freelance reporter through family connections he was one of the first to “train on the job” under the supervision of his father, John. By 1834 he’d spent a brief period at the True Sun, an evening paper, before transferring back to The Mirror of Parliament and then on to the leading Liberal newspaper of the day, the Morning Chronicle, a bigger paper rivalling The Times. He started to do more general reporting and was sent out to cover elections. With new contacts in the press he was able to publish a series of sketches under the pseudonym ‘Boz’. In April 1836, he married Catherine Hogarth, daughter of George Hogarth who edited ‘Sketches by Boz’. Within the same month came the publication of the highly successful ‘Pickwick Papers’, and from that point on there was no looking back for Dickens.

Certainly when Dickens started as a gallery reporter in 1830-31 the conditions were extremely grim. The Commons of the early 1830s was far smaller than that of today. It was cramped, claustrophobic and very poorly lit, making it almost impossible for the reporters to see who was speaking at night. Another issue was the overpowering stench from the river Thames – then the world’s largest open sewer. James Grant, a reporter who worked alongside Dickens, famously likened the old Commons to “the black hole of Calucutta”.

Reporting on parliament was an extremely difficult job. There was no dedicated press gallery before 1835, and reporters had to reserve spaces in the strangers’s gallery at the back of the Commons, writing with their notes perched on their knees, barely able to hear what was happening above the din of the chatter and the heckling. This is how Dickens described the conditions during a speech to the Newspaper Press Fund in May 1865:

” I have worn my knees by writing on them on the old back row of the old gallery of the House Of Commons; and I have worn my feet by standing to write in a preposterous pen in the old House of Lords, where we used to be huddled together like so many sheep”.

Another challenge for reporters like Dickens, was that most of the sittings occurred at night and many of them dragged on until the small hours of the mornings. Each reporter would usually work for up to an hour taking shorthand notes, and then have to spend the next four to five hours writing it all up.

When Parliament burned down in 1834 it’s not clear whether Dickens reported on it, because there were no bylines on news stories back then. After the fire, conditions for reporters in the Commons improved . Mps moved their sessions into the old house of Lords which was slightly larger and crucially, had a dedicated press gallery for the first time, located behind the speaker, which made seeing and hearing what was going on far easier.

His years as a Westminster reporter may have furnished him with many a tale and character for his subsequent novels, but by all accounts he was not impressed with the place and when he was later invited to become an MP he declined. Andrew Sparrow , author of Obscure Scribblers – A History of Parliamentary Journalism notes that “Dickens may have found his late-night deadline-chasing exhilarating, but he did not enjoy covering debates, and during his time in the gallery he developed a lifelong aversion to parliamentary pompositity. In David Copperfield, his autobiographical novel, his hero becomes a parliamentary reporter. ‘Night after night, I record predictions that never come to pass, professions that are never fulfilled, explanations that are only meant to mystify,’ says David. ‘ I am sufficiently behind the scenes to know the worth of political life. I am quite an Infidel about itit and shall never be converted’. Dickens felt the same way and, after leaving the commons, he said he would never return because he could not bear to listen to another worthless speech. ”

The five years that Dickens worked as a reporter were some of the most dramatic in British political history, dominated by an intense battle over parliamentary reform and the Great Reform Act of 1832 which completely gripped the nation. Dickens would also have witnessed the introduction of the new Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834 setting up a wave of workhouse construction, workhouses in which husbands, wives and children would subsequently be separated from each other. This of course became one of the major institutions of the Victorian era.

According to Dr Philip Salmon, from the History of Parliament trust, reports of what MPs said were one of the most widely read and celebrated items of the Victorian era. “Verbatim accounts appeared on the front pages of all the leading daily papers and were even sold separately by commercial publishers like Hansard, ” he says. ” Over 2 million people read Commons debates on a regular basis and exchanges between famous MPs became one of the mass entertainments of the age. Dr Salmon concludes that “Dickens role as a reporter at this crucial time would have given him a really intimate knowledge of all the leading components shaping Victorian society – the Commons really was the hub of the nation during this period and the centre of developments at the local and national level. It also gave him crucial experience in writing for one of the mass entertainments of the age”.